Have you ever found yourself in an overstimulating situation, unable to focus at the task at hand, unsure which input should be the center of your attention? Do you remember the sense of frustration and distraction, perhaps even being overwhelmed by your environment? Now imagine feeling like that all the time in almost every situation.

Worse yet, imagine being a child who feels like that. Imagine having no frame of reference for how you feel or how you process the world happening around you. Imagine being unable to explain what’s happening to you, incapable of articulating your profound bewilderment with stimuli and processes that don’t seem to faze those around you. Imagine being in a classroom that’s structured around the fundamental concept of sitting still in a chair for several hours and learning by rote, and simply struggling just to get through the day, to fight off that feeling of wanting to get up and move or make noise. Imagine enduring the confusion and even scorn of teachers and classmates who don’t understand why you can’t just be normal or what they perceive as normal, anyway.

That’s what it was like for Ben Lorber. As a small child, he was unable to crawl and started walking later than most children. He couldn’t speak on his own and had to be taught to make  sounds that come naturally to most of us. His struggles to articulate himself were such that at one point he even resorted to trying to make up his own sign language. The problem was a severe motor planning disorder that was unfortunately impossible to diagnose until he reached the age of five. Even after that, the difficulties continued. Despite the fact that he entered kindergarten in one of the best public school systems in Vermont with an individualized education program, Ben needed attention and accommodations that the school was unable to provide. He was overwhelmed by his environment and couldn’t sort out what he should pay attention to or how he should respond. It would build to the point that he would simply shut down or act out.

sounds that come naturally to most of us. His struggles to articulate himself were such that at one point he even resorted to trying to make up his own sign language. The problem was a severe motor planning disorder that was unfortunately impossible to diagnose until he reached the age of five. Even after that, the difficulties continued. Despite the fact that he entered kindergarten in one of the best public school systems in Vermont with an individualized education program, Ben needed attention and accommodations that the school was unable to provide. He was overwhelmed by his environment and couldn’t sort out what he should pay attention to or how he should respond. It would build to the point that he would simply shut down or act out.

“Ben was a very frustrated little boy,” recalls his mother, Leslie. She resorted to homemade fixes to alleviate his problems, providing him with vests loaded down with weights or weights he could lay on his lap to keep him in place. She was at the school nearly every day, trying to manage the times when he would shut down. Ben had trouble with sequencing, so she drew him a map of the bases in tee ball. The school provided him with an aide and put him into social skills classes, but being there twice a week with one other student just wasn’t enough. In second grade, Ben said that he was going to be “a stupid man” when he grew up. Despite the best efforts of both parent and school, Leslie remembers, “I knew this wasn’t going to work.” That’s when, almost by chance, she discovered the Wolf School in East Providence. It’s a place designed expressly for kids like Ben, kids with complex, often interlocking problems that defy easy diagnoses or categorizations like “special needs.” They’re kids that traditional schools often give up on, branding them as having “behavioral problems” that are actually symptoms of an underlying condition. Towards the end of second grade, Leslie brought Ben to the Wolf School for a visit. “He came here and fell to pieces,” she recalls. “This was the norm, but the difference was what they did about it.” Wolf School teachers and administrators are used to reactions like Ben’s and know how to work through them – or perhaps more accurately, learn how to work through them. “It’s almost like our teachers are detectives,” explains Marie Esposito, the school’s Director of Institutional Advancement. “Every day they figure out, what do the students need? How do they tick?” When Ben “fell to pieces” this time, the staff of the Wolf School invested the time to figure out what makes him tick. The Lorbers moved to Rhode Island three weeks later.

That’s when, almost by chance, she discovered the Wolf School in East Providence. It’s a place designed expressly for kids like Ben, kids with complex, often interlocking problems that defy easy diagnoses or categorizations like “special needs.” They’re kids that traditional schools often give up on, branding them as having “behavioral problems” that are actually symptoms of an underlying condition. Towards the end of second grade, Leslie brought Ben to the Wolf School for a visit. “He came here and fell to pieces,” she recalls. “This was the norm, but the difference was what they did about it.” Wolf School teachers and administrators are used to reactions like Ben’s and know how to work through them – or perhaps more accurately, learn how to work through them. “It’s almost like our teachers are detectives,” explains Marie Esposito, the school’s Director of Institutional Advancement. “Every day they figure out, what do the students need? How do they tick?” When Ben “fell to pieces” this time, the staff of the Wolf School invested the time to figure out what makes him tick. The Lorbers moved to Rhode Island three weeks later.

The Wolf School began in 1999 with three students, one classroom and two parents on a mission. Andrew Wallerstein, Mary Sloane and their son Otto faced the same dilemma that the Lorbers did: a child with complex problems and a school ill-suited to deal with them. Even in the best schools, students like that can often slip through the cracks. Work- ing with a teacher, a speech coach and an occupational therapist, they devised an immersion model for dealing with the unique learning needs of children like Otto and put that model to work in a rented classroom in the Jewish Community Center on the East Side. The premise, as current Head of School Anna Johnson articulates it, was simple: “Meeting the child where they are.”

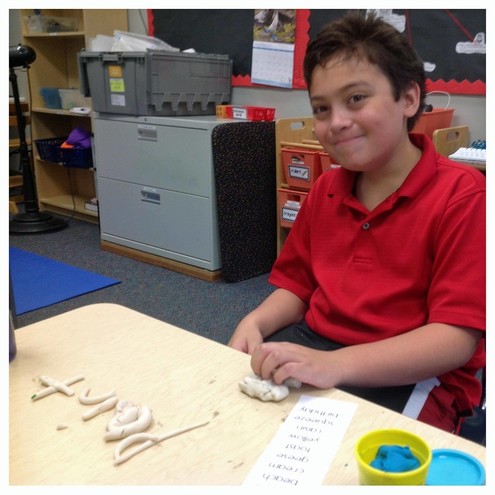

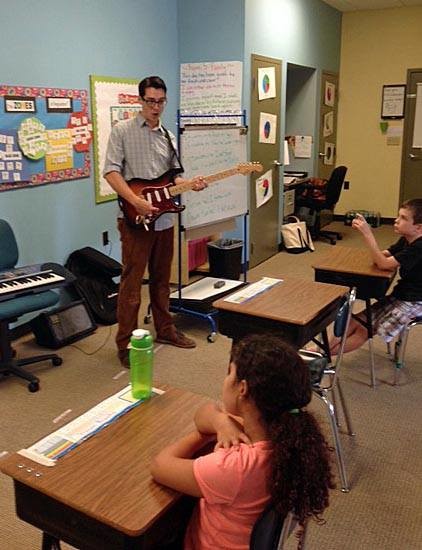

Johnson began as a teacher during the Wolf School’s early days in the JCC. The mission and model were novel – and still are. “We designed the model as we went,” she recalls. “There was no curriculum. We knew we needed to immerse them in this environment and the kids kind of designed the curriculum. We gave them what they needed.” The curriculum is guided by the teacher, and incorporates speech and occupational therapy. Movement is a huge part of the Wolf School philosophy, and manifests in a number of ways. Students move every 30-60 minutes to keep them active and engaged. But they don’t simply move between learning, they also move while learning. A typical Wolf School day might include learning to solve math problems on a rock climbing wall, or therapeutic horseback riding.

Of course, the term “typical Wolf School day” is kind of an oxymoron. With such an immersive model designed to adapt to so many individual learning styles, there is no such thing as a typical day. “There is no end point,” Johnson says of the school’s approach to curriculum. “It’s constantly evolving. We never know what to expect.” Esposito elaborates, explaining that the school’s model is not so much about learning a specific curriculum as it is about learning, period. “The kids are taught how to learn, how to deal with their differences,” she says. “They need to understand who they are as learners before they can begin to learn.”

After the inaugural 1999-2000 school year, Wolf grew by about a classroom a year until 2004, when it moved out of the JCC and into its current East Providence home. In 2005, it added the Pelson Center Gym and Sensory Arena. This unique facility allows students to more fully learn through movement. The gym and arena are designed to accommodate children who can be easily overwhelmed by environmental stimuli – it’s much quieter and more hospitable than the harsh, echoing spaces you might remember from your own school years. In those friendly confines, children who struggle with motor skills can practice things like “pillow polo” or engage in activities like the aforementioned rock wall math lesson. At present, the Wolf School boasts its highest ever enrollment, with 55 students spread across eight classrooms ranging from kindergarten to eighth grade. Approximately a third of those students are more traditional private school enrollments (albeit with nontraditional needs); another third receive financial aid; and the final third are out-of-district enrollments: students from public schools that are not equipped to accommodate the child’s needs. Those enrollments are funded by the respective school districts.

At present, the Wolf School boasts its highest ever enrollment, with 55 students spread across eight classrooms ranging from kindergarten to eighth grade. Approximately a third of those students are more traditional private school enrollments (albeit with nontraditional needs); another third receive financial aid; and the final third are out-of-district enrollments: students from public schools that are not equipped to accommodate the child’s needs. Those enrollments are funded by the respective school districts.

Despite the adaptive curriculum, the Wolf School maintains rigorous stan- dards. It is accredited for special education and abides by Common Core. Teachers are given ample planning time to collaborate, compare notes, and address the unique and varied challenges of the student body. At any given time, teachers might be applying six or seven different approaches to reading so that no student is allowed to slip through the cracks. The end goal is to prepare students to move beyond the Wolf School and work towards, “whatever success means for them,” as Johnson puts it. They’ve had over 70 alumni successfully move on from the school. One graduated from a four-year college and may pursue a master’s in social work. Another is currently in a traditional high school and thinking about starting a business after graduation. Another is a volunteer firefighter and hoping to pursue it professionally. Still another arrived in third grade unable to tie his own shoes, and by eighth grade starred in the school play and was reading at grade level.

And then there is Ben Lorber. Despite his prediction that he would grow up to be “a stupid man,” Ben is in his second year at Bard College, studying Russian and pursuing journalism and human rights. He’s looking into an internship in Budapest, Hungary. Perhaps even more interesting is the ripple effect of his experience: his sister is now planning to become an occupational therapist. “I don’t think he’d be where he is today without Wolf,” Leslie says. “It’s a special place.”

The Wolf School

215 Ferris Avenue, Rumford

401-432-9940

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here